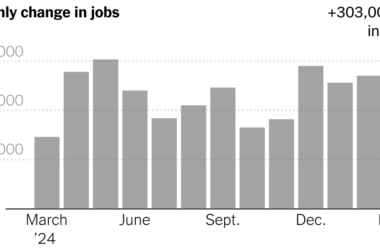

Halfway through the year, and four years removed from the downturn set off by the coronavirus pandemic, the U.S. job engine is still cruising — even if it shows increased signs of downshifting.

Employers delivered another solid month of hiring in June, the Labor Department reported on Friday, adding 206,000 jobs in the 42nd consecutive month of job growth.

At the same time, the unemployment rate ticked up one-tenth of a point to 4.1 percent, up from 4 percent and surpassing 4 percent for the first time since November 2021.

The gain in jobs was slightly greater than most analysts had forecast. But totals for the two previous months were revised downward, and the uptick in unemployment was unexpected. That has led many economists and investors to shift from having full faith in the jobs market to having some concern for it.

“These numbers are good numbers,” said Claudia Sahm, the chief economist for New Century Advisors, cautioning against overly negative interpretations of the report.

But “the importance of the unemployment rate is it can actually tell us a bit about where we might be going,” she added, noting that the rate had been drifting up since hitting a half-century low of 3.4 percent early last year.

Wage gains have also been moderating. Average hourly earnings rose 0.3 percent in June from the previous month, and 3.9 percent from a year earlier, compared with a 4.1 percent year-over-year change in May. But in good news for workers, pay gains have been outpacing inflation for about a year.

The market response to the report on Friday was muted, with stocks rising modestly. Yields on government bonds fell, however, reflecting traders’ increasing confidence that the Federal Reserve will begin cutting interest rates.

The benchmark interest rate, near zero at the start of 2022, has now been above 5 percent for more than a year in the Fed’s push to get inflation under control. The impact on lending across the economy has persisted longer than many businesses — or households looking to buy a house or a car — had reckoned.

Most economists expect further deceleration in job and wage growth until the Fed acts to ease credit conditions. There is growing evidence of slowing.

Layoffs are near record lows, but an indicator known as the hiring rate — which tracks the number of hires during a month as a share of overall employment — has fallen significantly. This means that the relatively few people losing their jobs are, in general, having more trouble finding new opportunities.

Roughly three-quarters of the job gains in the June report came from health care, social assistance and government. A few other industries produced scant increases, and some, including manufacturing and retail, shed jobs overall.

Much of the government hiring is part of a long-anticipated catch-up by state and local governments, which have lamented understaffing and only recently recovered to their prepandemic employment peaks. And the aging of the American population has created consistently high demand for health care workers and other care work.

Economists tend to feel more confident, though, when the bulk of employment gains are coming from sectors more indicative of private-sector momentum.

“Job postings are trending down,” said Nick Bunker, an economic research director at the recruitment site Indeed.

That may partly explain why the ranks of the long-term unemployed — those out of work for 27 weeks or more — is now above its 2017-19 average.

With inflation at 2.6 percent, not far from the Fed’s target of 2 percent, some analysts are worried that the central bank’s current stance could end up upending the job market. Fed officials have signaled over the past month that they would react to a suddenly weakening labor market by cutting rates, which are currently at a decades-long high.

Policymakers at the Fed will meet later this month and again in September to set rate policy. Some investors and financial analysts reacting to the June employment numbers said officials should not risk waiting too long.

“Conditions in the labor market are cooling off,” said Neil Dutta, the head of economic research at Renaissance Macro Research, a financial firm. “The trade-offs for the Fed have shifted. If they don’t cut this month, they ought to make a strong signal a cut is coming in September.”

As the financial world awaits the next move, U.S. households have continued to spend at a healthy, if somewhat subdued, tempo. In the past month, the Transportation Security Administration screened a record number of travelers at airports. Recent corporate earnings reports suggested that consumers, while pickier than before, remained in good shape overall. Since the start of the year, the stock market has reached fresh highs, recording an impressive 17 percent return.

In many ways, the financial picture for American households is brighter than it was before the pandemic. At the end of 2019, U.S. households held roughly $980 billion in “checkable deposits” — the sum of cash assets in checking, savings and money market accounts. Now, the figure stands at more than $4 trillion.

While that wealth is concentrated toward the top overall, wealth and income gains have been widespread. The net worth held by the bottom 50 percent of households, about $1.9 trillion on the eve of the pandemic, is now around $3.8 trillion. And for workers who are not managers — roughly eight of 10 people in the work force — wage growth has been far stronger than the overall average.

For privately owned businesses with fewer resources than those of large corporations, the economy of the last four years has sometimes presented a nauseating roller coaster of challenges. That’s been the case for the brothers Mazen and Afif Baltagi, who own a variety of hospitality businesses in the Houston area — an event space, a sports bar and a few cafes — along with some investment partners.

Crowds are not quite what they were in 2021 and 2022, when people were spending with more euphoria. And “it’s not an easy business,” Mazen Baltagi said, especially since food, labor and construction costs have jumped and largely stayed elevated.

Still, from his vantage point, “Texas is booming.”

In this interest-rate environment, “banks aren’t really lending to restaurants right now,” he added, but he said he and his brother were working around that, making enough in sales — and from new equity partners — to undertake upcoming expansions.

That combination of adaptability and profitability among businesses is a sample of the forces that helped the United States avoid the recession that many experts expected. But surveys of business executives suggest that many are waiting for the cost of credit to fall before diving into new waves of hiring or capital investments.

Now the question, it seems, is whether the Fed will cut interest rates in time to keep the expansion going. Additional data reports about consumer prices will prove crucial as the summer rolls on.

The financial markets “just need the inflation data to cooperate,” said Samuel Rines, an economist and macro strategist at WisdomTree, an investment management firm. “Then it’s game on.”